A second spell of temperatures well over 30C before we’ve even got to the end of June – how unusual is this and how much is climate change to blame?

Temperatures of 34C are possible on Monday or Tuesday in south-east England.

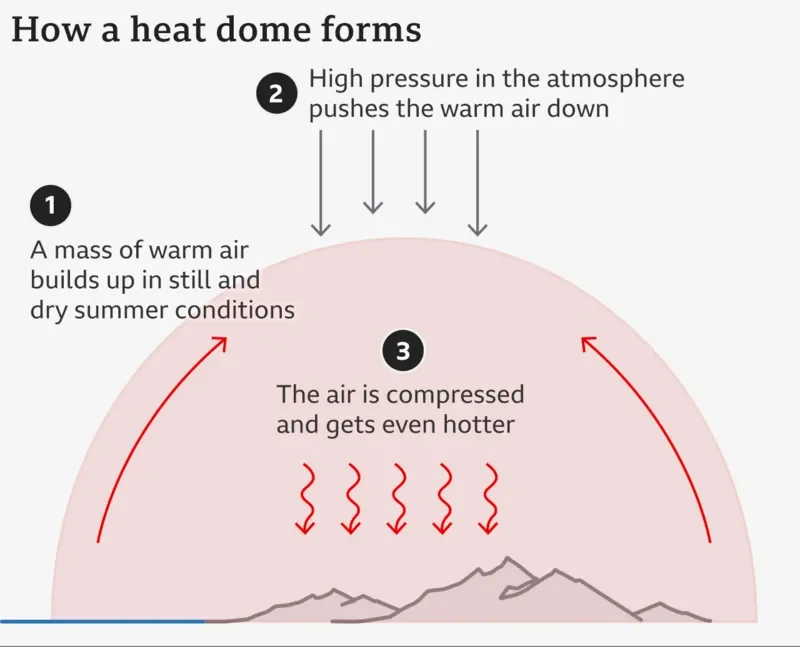

They’ve been triggered by an area of high pressure getting “stuck” over Europe, known as a heat dome.

But climate scientists are clear that the heat will have inevitably been boosted by our warming climate.

Some people might feel these temperatures are “just like summer” – and it’s true they are a lot cooler than the record 40C and more the UK hit in July 2022.

But it’s important to be aware just how unusual mid-thirties temperatures are for the UK.

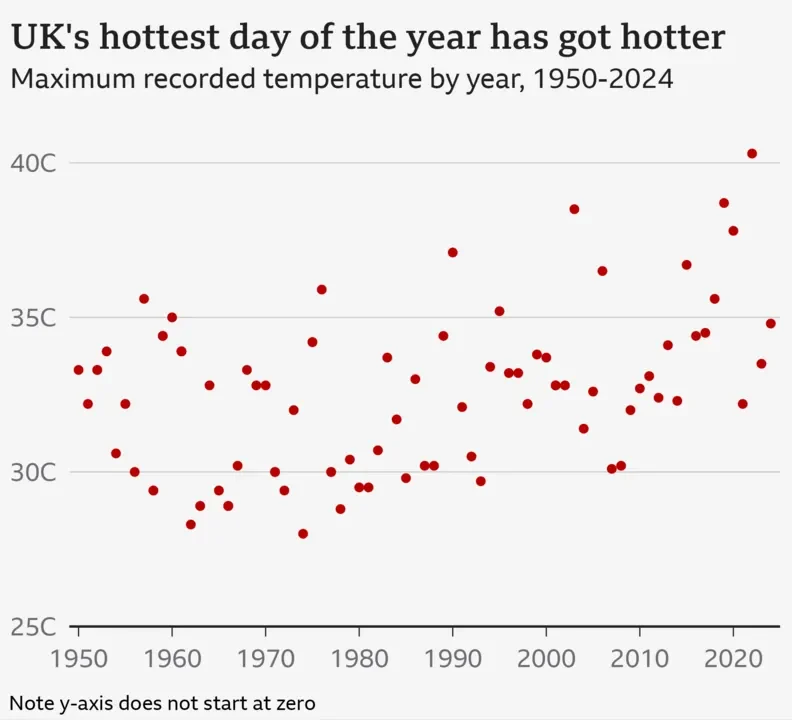

In the second half of the 20th Century, one in ten years saw highs of 35C or more, BBC analysis of Met Office data shows.

But this heat is becoming more common. Between 2015 and 2024, half of the years saw 35C or above.

And these temperatures are particularly unusual for June, typically the coolest summer month.

“Recording 34C in June in the UK is a relatively rare event, with just a handful of days since the 1960s,” said Dr Amy Doherty, climate scientist at the Met Office.

The hottest June temperature recorded since 1960 is 35.6C in 1976. The next years on the list are 2017 with a June high of 34.5C and 2019 with 34.0C.

Forecasts suggest that 2025 could come close to those.

And further data from the Met Office also shows that over the decade 2014-2023, days exceeded 32C more than three times as often in the UK as during the 1961-1990 period.

Role of climate change

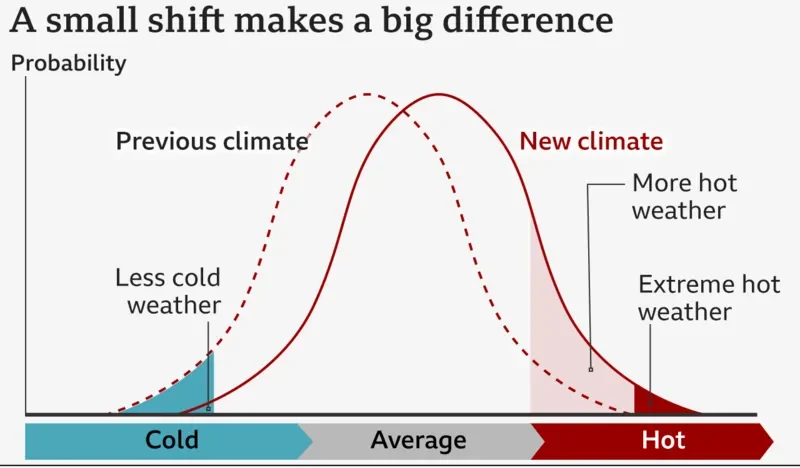

It is well-established that climate change is making heatwaves stronger and more likely.

As humans burn coal, oil and gas and cut down forests, carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases are released into the atmosphere.

These gases act like a blanket, warming the Earth.

So far humans have caused the planet to heat up by 1.36C above levels of the late 1800s, leading scientists reported earlier this month.

That might not sound a lot. But even a small increase in the Earth’s average temperature can shift heat extremes to much higher levels.

It will take time to work out exactly how much climate change has added to this heatwave’s temperatures. But scientists are clear that it will have boosted the warmth.

“We absolutely do not need to do an attribution study to know that this heatwave is hotter than it would have been without our continued burning of oil, coal and gas,” said Dr Friederike Otto, associate professor at Imperial College London.

“Countless studies have shown that climate change is an absolute game-changer when it comes to heat in Europe, making heatwaves much more frequent, especially the hottest ones, and more intense,” she added.

Scientists are still debating how climate change is affecting the formation of heat domes, the immediate cause of the heatwave.

One theory suggests that higher temperatures in the Arctic – which has warmed nearly four times faster than the global average – are affecting the fast band of winds high in the atmosphere known as the jet stream, making heat domes more likely.

That is far from certain, but the basic effect of warming the planet makes heat domes more intense when they do form.

“What is crystal clear is that climate change is loading the dice such that when a heat dome does occur, it brings hotter and more dangerous temperatures,” said Dr Michael Byrne, reader in climate science at the University of St Andrews.