Three hundred years since they first appeared, the capital’s traditional members-only gentlemen’s clubs – still frequented by royalty and power brokers – have endured and evolved. As controversy continues around The Garrick permitting women members, a new book explores this peculiarly British phenomenon.

For more than three centuries, London has been the global centre of private members’ clubs. In no other place have so many of these secretive sanctuaries come and gone, and today, with a total of 133 operating, the British capital still outstrips its closest rival, New York City, which hosts a mere 53 clubs.

Many of the historic men-only London clubs have moved with the times, and now allow female members. And arguably the most famous in traditional clubland, The Garrick Club, founded in 1831, made the news last year when it finally decided to drop its men-only rule. Since then, however, only a handful of women has been elected as members there, and, last month, broadcast journalist Julie Etchingham withdrew her candidacy. Reportedly, some prospective female candidates are uncomfortable with the protracted vetting process and seeming hostility of numerous members to women joining. The Savile Club voted earlier this year to keep women out. Hidebound attitudes remain, it seems.

Clubs speak to something deeply-rooted in human character the world over, and in the UK they have special resonance

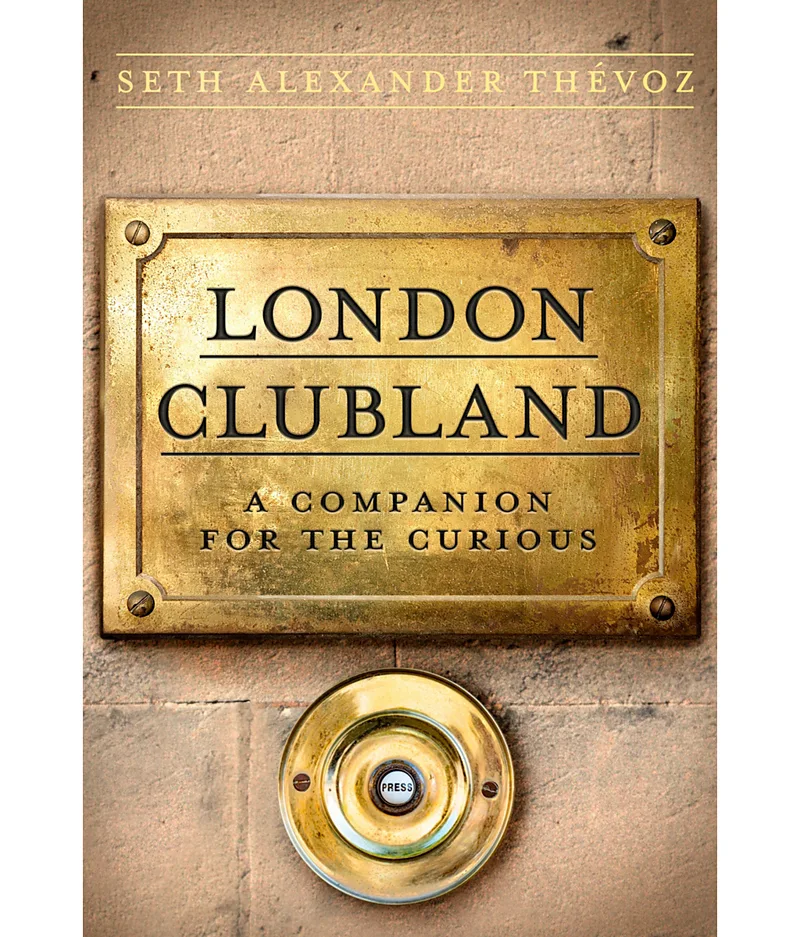

Now a new book, London Clubland: A Companion for the Curious, by Dr Seth Alexander Thévoz, provides a club-by-club overview, along with a deep dive into their particularities – customs, rules, traditions and even a few recipes. Clubs have often needed to evolve in order to survive, Thévoz reveals, and those that endure tend to serve a distinct membership.

The author believes that while clubs speak to something deeply-rooted in human character the world over, in the UK they have special resonance. He tells the BBC: “The British have always liked the certainty of club membership, and have been hugely into associational culture, from young people joining the Scouts and Girl Guides, to older people volunteering for an amateur dramatics society.”

How it began

It all started with coffee. In the second half of the 17th Century, when coffee drinking was first introduced to England, coffee houses were a welcome alternative to taverns and became associated with good conversation. Samuel Pepys wrote in December 1660 of his evening at the “Coffee-house” in Cornhill: “I find much pleasure in it through the diversity of company – and discourse.”

In 1693, an Italian migrant to London, Francesco Bianco (who anglicised his name to Francis White), opened an establishment that served both coffee and hot chocolate; he called it Mrs White’s Chocolate House. Patrons flocked to St James’s Street, not only for the hot beverages, but for the gambling room – the site of illegal, high-stakes card games – tucked away at the back of the premises. White’s is still operating, and is London’s oldest club. Only men are allowed to join. (King Charles counts among its 1500 members; he held his stag night at White’s before his 1981 wedding to Princess Diana.)

Numerous other clubs opened in this manner throughout the Georgian era, Thévoz notes, because gambling dens labelled “private members’ clubs” were more difficult for the authorities to raid. As the aristocratic membership increasingly demanded food and entertainment along with their gaming, hospitality professionals took over the management. Brooks’s (founded 1764) is another Georgian club that has survived to this day, along with Boodle’s (1762), originally called Almack’s. Boodle’s “is probably the best-preserved 18th-Century clubhouse”, Thévoz tells the BBC – passers-by can recognise it by its iconic front-facing bow window.

The Georgian London clubs were known less for political debate than for companionable eating and drinking. Conservative William Praed wrote of his time as an MP from 1774 to 1808:

In Parliament I fill my seat,

With many other noodles;

And lay my head in Jermyn Street

And sip my hock in Boodle‘s

Boom time

It was during the 19th Century that clubs in London boomed – approximately a dozen existed at the start of the century, and 400 by the end. Clubs in general became less louche, in step with a new, Victorian interest in propriety. Most significantly, they took on a central role in British politics, and scores of political clubs were founded in central London in these years, in a swathe of the city bound by Piccadilly to the north, Pall Mall to the south, St James’s Street to the west, and Haymarket to the east. Several of the most renowned, party-affiliated clubs have endured to this day. The Carlton Club, the Conservative stronghold, founded in 1832, was from the start a hotbed of gossip and political intrigue. The Duke of Wellington, at one time a member, advised on his deathbed: “Never write a letter to your mistress and never join the Carlton Club.”

The Reform Club was established in 1836 on Pall Mall to provide a hub for Whigs and Radicals, and later Liberals. It is also a setting in Around the World in Eighty Days, the 1872 novel by Jules Verne – the protagonist Phileas Fogg makes a £20,000 bet with six members that he can circumnavigate the globe and arrive back “in this very room of the Reform Club” in 80 days’ time.

‘The best club in London‘

When in October 1834 a massive fire destroyed the old Houses of Parliament, many of the functions of government relocated to the clubs. The new Palace of Westminster was modelled after a private members’ club, with tea rooms, smoking rooms and libraries, prompting Charles Dickens in 1864 to call the House of Commons “the best club in London”.

The prince, a dedicated bon viveur, got fed up with the amount of gossip that was leaking out of White’s about his amorous activities – and founded his own club

One of the first clubs open to both men and women, The Albemarle Club, founded in 1874, was associated from the start with the burgeoning women’s rights movement. It became notorious when member Oscar Wilde was confronted there by the Marquess of Queensbury, father of his lover Lord Alfred Douglas, in an incident that set off the ill-fated libel trial that would lead to Wilde’s conviction and imprisonment.

Royalty has always favoured London clubs, but none more enthusiastically than Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII. The prince, a dedicated bon viveur, got fed up with the amount of gossip that was leaking out of White’s about his amorous activities, Thévoz explains. The prince decided to found his own club, the Marlborough Club, named after his London residence, in 1869. He handpicked the first 400 members, and retained ultimate black-ball power, so he could veto the membership of anyone he didn’t trust.

At the dawn of the 20th Century, London clubs were still going strong, and providing fodder for fiction writers. According to Thévoz, the Drones Club featured in PG Wodehouse‘s work most closely resembles Buck’s Club in Mayfair, founded in 1919. The club was immediately popular for its US-style cocktail bar. The signature drink was, then and now, the Buck’s Fizz – Champagne and orange juice with a mysterious twist.

In 2023, conservative establishment Pratt’s surprised many by admitting women for the first time

Ian Fleming was a member of Boodle’s, upon which he based Blade’s club in his James Bond books. In Evelyn Waugh’s novel Brideshead Revisited, protagonist Charles Ryder gathers with friends at Bratt’s, most likely inspired by Pratt’s, a small supper club in St James’s founded in 1857, and owned since 1926 by the family of the Duke of Devonshire. In 2023, this most conservative of establishments surprised many by admitting women for the first time.

Clubs for women enjoyed a heyday in the last decade of the 19th Century and the first of the 20th, numbering 86 in all by Thevoz’s count. Some were patronised by wealthy women in town for shopping and the theatre. Others were residential, offering affordable accommodation to single women beginning careers in the capital. Muriel Spark, in her 1963 novel The Girls of Slender Means, based the May of Teck Club, where her protagonists live, on The Service Women’s Club.

Over the past 100 years, nine out of 10 of the venerable members’ clubs closed. The long period of decline – beginning roughly in the early 1920s and accelerating after World War Two – bottomed out in the 1970s. A change in social mores, a dwindling number of ageing members, and steeper fees all played their part in this downturn.

If the past is any guide, the London club, ever morphing, will continue to be a feature of life in the capital for the foreseeable future, an indication of its citizens’ abiding interest in conversation, eating and drinking in environs that in some way they can call their own.